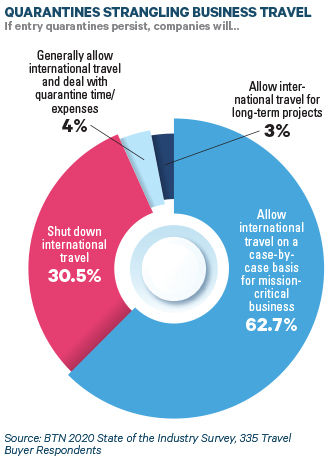

International business travel will not revive while visitors are routinely quarantined on arrival. That is the clear verdict of the 335 travel buyers polled as part of BTN’s 2020 State of the Industry Survey. An overwhelming 93 percent said that if quarantining persists as a precaution against coronavirus, their company would either allow international travel only on a mission-critical basis or disallow it entirely.

Quarantining after outbound or inbound foreign trips, or both, is almost ubiquitous worldwide, the usual period for isolation being 14 days. Stressful, unproductive and expensive, mandatory self-isolation has effectively made all but the most important international business journeys unconscionable. Even where a quarantine requirement is not in place, the fear it might be imposed (dubbed "quarantine bingo") deters all but a few.

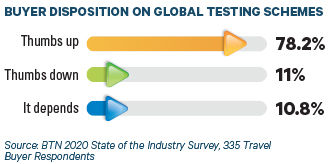

The travel industry is proclaiming increasingly loudly that testing passengers for coronavirus is the way out of the problem. Travel buyers agree: 79 percent of BTN’s survey respondents gave global testing schemes the thumbs-up, while 11 percent gave a thumbs-down and 11 percent indicated "it depends."

"Anything that’s simple and proves what travelers have would definitely resurrect people to come out and fly again," EY global head of travel, meetings and events Karen Hutchings told a BTN Europe podcast audience last month.

But while it might restore confidence in boarding an aircraft, numerous unresolved concerns expressed by governments, medical professionals and indeed some travel managers leave testing far from being the silver bullet that will restore unhindered business travel. The 11 percent who said "it depends" may have made the right call.

Can Industry & Governments Agree on Testing Protocols?

Part of the ambiguity rests on there being broadly two kinds of coronavirus testing. The first, an antigen test, is described as a "one-day pass" by David Sarafinas, VP of travel risk management at Collinson, which has introduced testing services at various airports. According to Dr. Adrian Hyzler, chief medical officer for risk management and medical assistance company Healix, an anitgen test detects if someone is contagious. "It shows whether there is enough virus in your nose and throat to infect other people," Dr. Hyzler said. "It’s a way of making people confident enough to get on a plane."

Antigen tests are cheap and results are available within minutes. The other kind of test is a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test, which is what hospitals use. It is highly accurate in detecting whether the virus is present in any quantity, even before a person becomes contagious, and is therefore more relevant to immigration authorities determining whether to admit a traveler.

However, PCR testing does present challenges. It is more expensive: Collinson charges $200 to $225, double its fee for antigen testing. Obtaining a result also takes much longer – usually measured in days rather than hours, although Sarafinas said Collinson is capable of a 24-hour turnaround in London and could potentially reduce to 3 to 5 hours if lab facilities were available at the test site.

Other questions arise. Speaking in the same BTN Europe podcast as Hutchings, Gray Dawes Group chief commercial officer David Bishop wondered how test data could be incorporated into managed travel systems. "This needs to be embedded into our ecosystem pretty quickly ... but how it fits into the GDS I don’t know," he said.

There would also have to be international acceptance of a testing regime. "Consistency is very important. Some countries won’t accept tests carried out in other locations," said a European travel manager, speaking on condition of anonymity.

But most importantly, will governments accept that PCR tests allow them to lift quarantine requirements? The answer in many cases looks to be no: Testing will reduce quarantines from the standard 14 days but not eliminate them. UK transport secretary Grant Shapps told an Association of British Travel Agents convention in October that his government is working on testing after one week of quarantine, paid for by the passenger.

According to Hyzler, two studies have shown not all infected passengers can be caught through screening on arrival but can safely be released after seven days. The more recent, and larger, study, backed by Air Canada, saw 13,000 passengers self-test on day of arrival at a destination and then seven and 14 days later. Of the 1 percent who tested positive, 80 percent tested positive on day of arrival, 20 percent seven days later and none on day 14.

"I do not see a way around a seven-day quarantine, especially for travelers coming from a country with a high prevalence of Covid," said Hyzler. "But if someone is coming from China, there is no reason for quarantine."

Are There Reasonable Risks?

As this last remark implies, trade-offs between total infection risk elimination and getting economies moving again are likely. Japan and South Korea have already lifted quarantining requirements for short-term business travellers who test negative on arrival, and there are reports of planned "air bridges" from the U.S. to the UK and Germany. Governments are also mindful that quarantines are hard to police: Many individuals ordered to self-isolate fail to do so.

Clive Wratten, chief executive of the UK’s Business Travel Association for travel management companies, is optimistic testing will help. "We are seeing other tests coming down the line that are quicker and more accurate and that’s when we will get business moving again, but I think PCR tests can work now and that shouldn’t preclude us from going ahead," he said. "There are a number of people who want to start traveling now."

But do they? "Quarantining is one reason businesspeople don’t want to travel but it’s not the only one," said Jörg Martin, principal of CTC Corporate Travel Consulting in Germany.

Harriet Washburn, Rolling Meadows, Il.-based sourcing director for Gallagher, agrees. "People are concerned for their own safety [if they have to travel] and the people they are proposing to meet are concerned about meeting them; and the offices where they would normally meet are closed anyway," she said. "My concern is a test is only good for the time when a person is tested. Travelers could be exposed at the business meeting and then they could expose others on return. It’s not a panacea that opens the floodgates and lets people go back to traveling."

Washburn believes business travel will only start to return substantially once a vaccine is widely available. Hyzler agrees but warns that trial and error, literally, make establishing an effective vaccination regime a lengthy process, even if the first vaccines are introduced very soon. "Pandemics don’t go out with a bang; they fade with a whimper," he said. "I imagine it will be into 2022 before we are in control of this."