A critical but often overlooked determinant of

how much companies pay for business travel is exchange rates. In 2022, the big

story in currency movements was the strengthening of the U.S. dollar, a direct

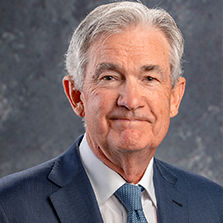

consequence of the interest rate strategy set by Jerome Powell at the helm of

the Federal Reserve.

By the beginning of March, inflation in the

U.S. had reached 8 percent. Fed policy is to try to limit inflation to 2 percent,

so Powell reached for the biggest lever at his disposal: raising interest

rates. Since March, the Fed has pushed rates up from just above zero to nearly

4 percent, including four consecutive months of 0.75-point increases from

August to November, the steepest hike since the early 1980s.

When a country raises its interest rates,

foreign capital flows in, driving in turn the appreciation of its currency.

Sure enough, that happened to the dollar. Against the euro the greenback

appreciated from €0.89 in March to a high of €1.04, although it since has

receded to €0.95. Against sterling the dollar was already at an historic high of

£0.75 in March and then soared to a jaw-dropping £0.93 during the brief but

disastrous U.K. premiership of Liz Truss, before settling back to £0.82 at time

of writing.

For business travelers visiting the U.S., the

hardening of the dollar has added even more financial agony on top of the pain

of underlying inflation in hotel, restaurant and car rental pricing. For U.S.

business travelers visiting everywhere else, the dollar’s strength has gone a

long way to mitigating that inflationary pain.

But business travelers everywhere also pay more

because the majority of input costs in global aviation—an estimated 60 percent

for long-haul carriers—are priced in dollars, including fuel and aircraft

leasing. It is a complicated picture because airlines hedge their exchange

rates, and there are many other inflationary pressures. However, the rampage of

the dollar unleashed by Powell has undoubtedly contributed to a CWT/Global

Business Travel Association assessment that global airfares have shot up 40-odd

percent in 2022.

Powell is one of that increasingly rare breed

of Republicans who look for bipartisan consensus, explaining why Joe Biden gave

him a second four-year term as Fed chair after originally being installed by

Donald Trump. He generally is regarded as having had a good pandemic.

But those hoping Powell may soon soften the

dollar by changing his interest rate strategy are likely to be disappointed.

“By any standard, inflation is much too high,” he declared on Nov. 30. “I will

simply say that we have more ground to cover.”